§Starting up the project

§Introduction

In this tutorial you will learn the Play 2 Framework by coding a real web application, from start to finish. In this application, we will try to use everything you would need in a real project, while introducing good practices for play application development.

We have split the tutorial into several independent parts. Each part will introduce more complex features, and provide everything that a real project needs: validation, error handling, a complete security framework, an automated test suite, a shiny web interface, an administration area etc.

All the code included in this tutorial can be used for your projects. We encourage you to copy and paste snippets of code or steal whole chunks.

§The project

We are going to create a task management system. It’s not a very imaginative choice but it will allow us to explore most of the functionality needed by a modern web application.

We will call this task engine project ZenTasks.

This tutorial is also destributed as a sample application. You can find the final code in the

samples/java/zentasksdirectory of your play installation.

§Prerequisites

First of all, make sure you have a working Java installation. Play requires Java 6 or later.

As we will use the command line a lot, it’s better to use a Unix-like OS. If you run a Windows system, it will also work fine; you’ll just have to type a few commands in the command prompt.

We will assume that you already have knowledge of Java and Web development (especially HTML, CSS and Javascript). However you don’t need to have a deep knowledge of all the JEE components. Play is a ‘full stack’ Java framework and it provides or encapsulates all the parts of the Java API that you will need. No need to know how to configure a JPA entity manager or deploy a JEE component.

You will of course need a text editor. If you are accustomed to using a full featured Java IDE like Eclipse or IntelliJ you can of course use it. However with play you can have fun working with a simple text editor like Textmate, Emacs or VI. This is because the framework manages the compilation and the deployment process itself, as we will soon see…

Later in this tutorial we will use Lighttpd and MySql to show how to deploy a play application in ‘production’ mode. But Play can work without these components so if you can’t install them, it’s not a problem.

§Installation of the play framework

Installation is very simple. Just download the latest binary backage from the download page and unzip it to any path.

If you’re using windows, it is generally a good idea to avoid space characters in the path, so for example

c:\playwould be a better choice thanc:\Documents And Settings\user\play.

To work efficiently, you need to add the play directory to your working path. It allows you to just type play at the command prompt to use the play utility. To check that the installation worked, just open a new command line and type play; it should show you the play basic usage help.

§Project creation

Now that play is correctly installed, it’s time to create the task application. Creating a play application is pretty easy and fully managed by the play command line utility. That allows for standard project layouts between all play applications.

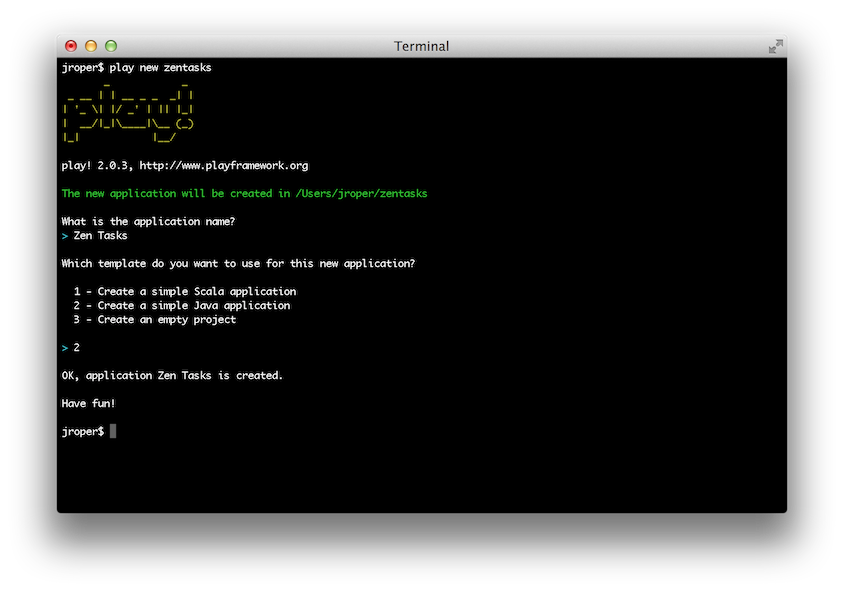

Open a new command line and type:

~$ play new zentasks

It will prompt you for the application full name. Type ‘ZenTasks’. It will then prompt you for a template to use. We are creating a Java application, so type 2.

Whether you select Java or Scala now, you can always change it later.

The play new command creates a new directory zentasks/ and populates it with a series of files and directories, the most important being:

app/ contains the core of the application, split between models, controllers and views directories. It can contain other Java packages as well.

conf/ contains all the configuration files for the application, especially the main application.conf file, the routes definition file and the messages files used for internationalization.

public/ contains all the publicly available resources, which includes Javascript files, stylesheets and images directories.

project/ contains the project build files, which is in particular where you can declare dependencies on other libraries and plugins for the play framework.

test/ contains all the application tests. Tests are written either as Java JUnit tests or as Selenium tests.

Because play uses UTF-8 as the single encoding, it’s very important that all text files hosted in these directories are encoded using this charset. Make sure to configure your text editor accordingly.

Now if you’re a seasoned Java developer, you may wonder where all the .class files go. The answer is nowhere: play doesn’t use any class files; instead it reads the java source files directly. Under the hood we use the SBT compiler to compile Java sources on the fly.

That allows two very important things in the development process. The first one is that play will detect changes you make to any Java source file and automatically reload them at runtime. The second is that when a Java exception occurs, play will create better error reports showing you the exact source code.

In fact play can keep a bytecode cache in the application

/targetdirectory, but only to speed up things between restart on large applications. You can discard this cache using theplay cleancommand if needed.

§Running the application

We can now test the newly created application. Just return to the command line, go to the newly created zentasks/ directory and type play. You have now loaded the Play console. From here, type run. Play will now load the application and start a web server on port 9000.

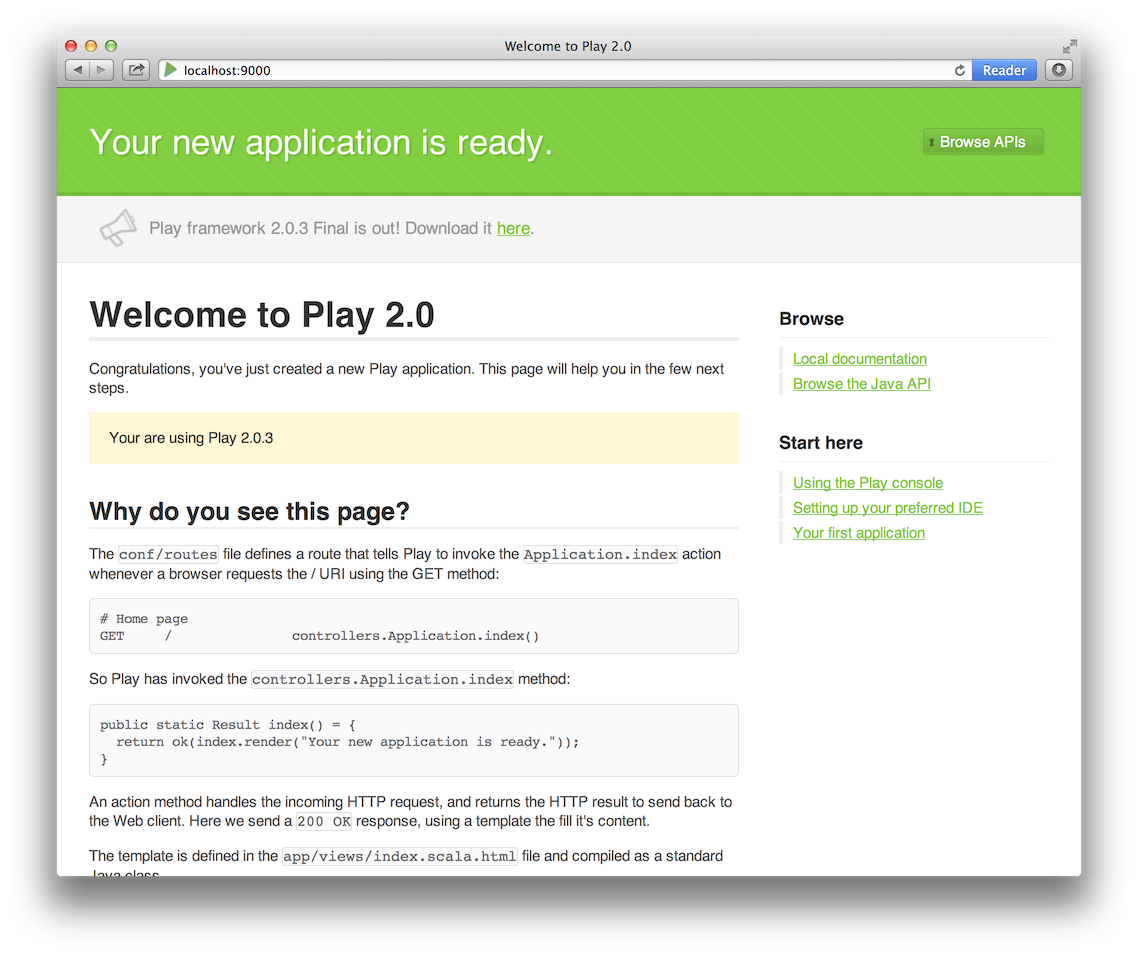

You can see the new application by opening a browser to http://localhost:9000. A new application has a standard welcome page and just tells you that it was successfully created.

Let’s see how the new application can display this page.

The main entry point of your application is the conf/routes file. This file defines all accessible URLs for the application. If you open the generated routes file you will see this first ‘route’:

GET / controllers.Application.index()

That simply tells play that when the web server receives a GET request for the / path, it must call the controllers.Application.index() Java method.

When you create standalone Java applications you generally use a single entry point defined by a method such as:

public static void main(String[] args) {

...

}

A play application has several entry points, one for each URL. We call these methods ‘action’ methods. Action methods are defined in special classes that we call ‘controllers’.

Let’s see what the controllers.Application controller looks like. Open the app/controllers/Application.java source file:

package controllers;

import play.*;

import play.mvc.*;

import views.html.*;

public class Application extends Controller {

public static Result index() {

return ok(index.render("Your new application is ready."));

}

}

Notice that the controller classes extend the play.mvc.Controller class. This class provides many useful methods for controllers, like the ok() method we use in the index action.

The index action is defined as a public static Result method. This is how action methods are defined. You can see that action methods are static, because the controller classes are never instantiated. They are marked as public to authorize the framework to call them in response to a URL. They always return play.mvc.Result, this is the result of running the action.

The default index action is simple: it calls the render() method on the views.html.index template, passing in the String "Your new application is ready.". It then wraps this in an ok() result, and returns it.

Templates are simple text files that live in the /app/views directory. To see what the template looks like, open the app/views/Application/index.scala.html file:

@(message: String)

@main("Welcome to Play 2.0") {

@play20.welcome(message, style = "Java")

}

The template content seems pretty light. In fact, all you see are Scala template directives.

The @(message: String) directive declares the arguments that this template accepts, in this case, it is a single parameter called message of type String. The message parameter gets used later in the template.

The @play20.welcome() directive is a call to the built in Play 2 welcome template that generate the welcome message you saw in the browser. You can see that it passes the message parameter that our arguments directive declared earlier.

The @main() directive is a call to another template called main.scala.html. Both the @play2.welcome() and the @main() calls are examples of template composition. Template composition is a powerful concept that allows you to create complex web pages by reusing common parts.

Open the app/views/main.scala.html template:

@(title: String)(content: Html)

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<title>@title</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" media="screen"

href="@routes.Assets.at("stylesheets/main.css")">

<link rel="shortcut icon" type="image/png"

href="@routes.Assets.at("images/favicon.png")">

<script src="@routes.Assets.at("javascripts/jquery-1.7.1.min.js")"

type="text/javascript"></script>

</head>

<body>

@content

</body>

</html>

Note the argument declaration, this time we are accepting a title parameter, and also a second argument called content of type Html. The second argument is in its own set of braces, this allows the syntax we saw before in the index.scala.html template:

@main("Welcome to Play 2.0") {

...

}

The content argument is obtained by executing the block inside the curly braces after the @main directive. You can see @content is then inserted between the <body> tags, in this way we have used template composition to wrap content from one template in another template.

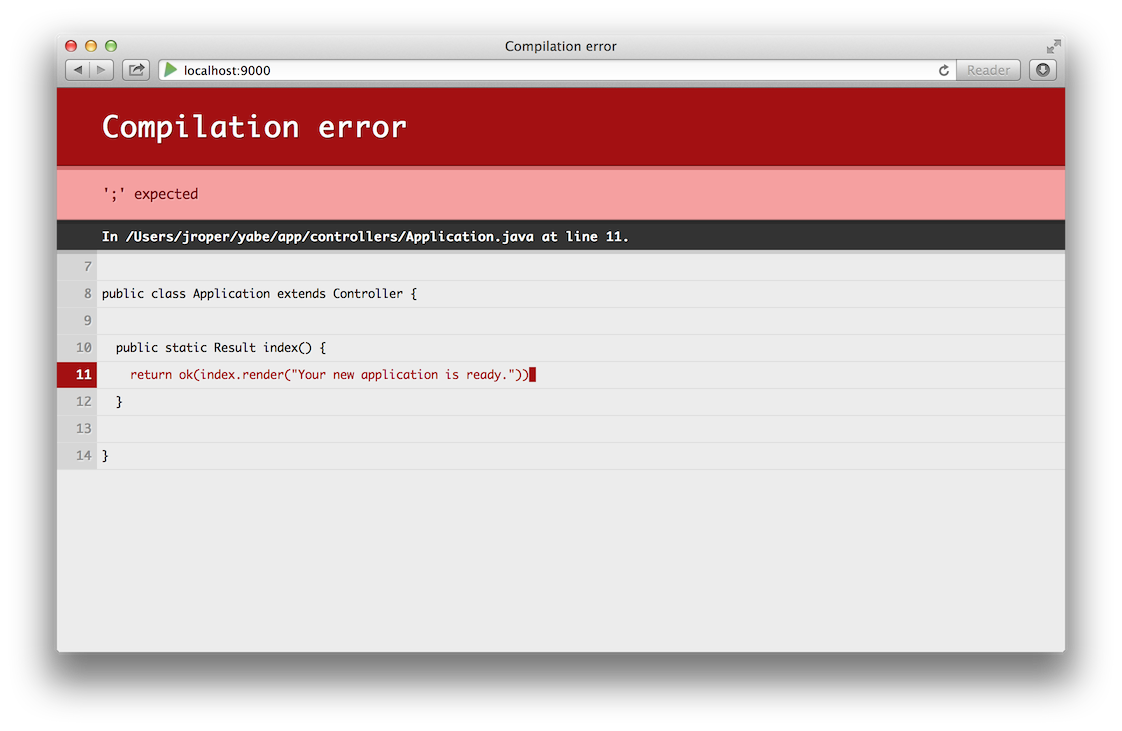

We can try to edit the controller file to see how play automatically reloads it. Open the app/controllers/Application.java file in a text editor, and add a mistake by removing the trailing semicolon after the ok() call:

public static Result index() {

return ok(index.render("Your new application is ready."))

}

Go to the browser and refresh the page. You can see that play detected the change and tried to reload the Application controller. But because you made a mistake, you get a compilation error.

Ok, let’s correct the error, and make a real modification:

public static Result index() {

return ok(index.render("ZenTasks will be here"));

}

This time, play has correctly reloaded the controller and replaced the old code in the JVM. The heading on the page now contains the updated text that you modified.

Now edit the app/views/Application/index.scala.html template to replace the welcome message:

@(message: String)

@main("Welcome to Play 2.0") {

<h1>@message</h1>

}

Like for the Java code changes, just refresh the page in the browser to see the modification.

We will now start to code the tasks application. You can either continue to work with a text editor or open the project in a Java IDE like Eclipse or Netbeans. If you want to set up a Java IDE, please check this page.

One more thing before starting to code. For the task engine, we will need a database. For development purposes, play comes with a standalone SQL database managements system called HSQLDB. This is the best way to start a project before switching to a more robust database if needed. You can choose to have either an in-memory database or a filesystem database that will keep your data between application restarts.

At the beginning, we will do a lot of testing and changes in the application model. For that reason, it’s better to use an in-memory database so we always start with a fresh data set.

To set up the database, open the conf/application.conf file and uncomment the following lines:

db.default.driver=org.h2.Driver

db.default.url="jdbc:h2:mem:play"

You can easily set up any JDBC compliant database and even configure the connection pool, but for now we’ll keep it at this. Additionally, we need to enable Ebean, so uncoment the following line:

ebean.default="models.*"

§Using a version control system (VCS) to track changes

When you work on a project, it’s highly recommended to store your source code in a VCS. It allows you to revert to a previous version if a change breaks something, work with several people and give access to all the successive versions of the application. Of course, you can use any VCS to store your project, but here we will use Git as an example. Git is a distributed source version control system, and Play has built in support for configuring a Play application inside a Git repository.

Installing Git is out of the scope of this tutorial but it is very easy on any system. Once you have a working installation of Git, go to the zentasks directory and init the application versioning by typing:

$ git init

Now add the root directory to the repository. You don’t need to worry about ignoring any files, Play has already automatically generated a .gitignore file that contains the appropriate list of files to ignore:

$ git add .

Finally you can commit your changes:

$ git commit -m "ZenTasks initial commit":

Our initial version is committed, and we have a solid foundation for our project.

Go to the next part